A viscous substance on your fingers leaves marks. It feeds you, it dirties you, it nourishes you, it

sickens you, it creates, it destroys, it resists to stay in place.

It’s soft to the touch, it’s malleable, it’s sticky, it flows, it drips, it pulls strings, it hardens,

eventually.

A seed, sowed by hand, creates life. It roots and it grows, it blossoms and it’s reaped. It’s

transformed, it’s conserved, it’s consumed and it rots.

A seed, stuck to your shoe, creates life in a different place. It roots and it grows, it blossoms and

it rots.

These last few turbulent months have been a time for self-reflection and I am using this show to

reflect on my work over the last years.

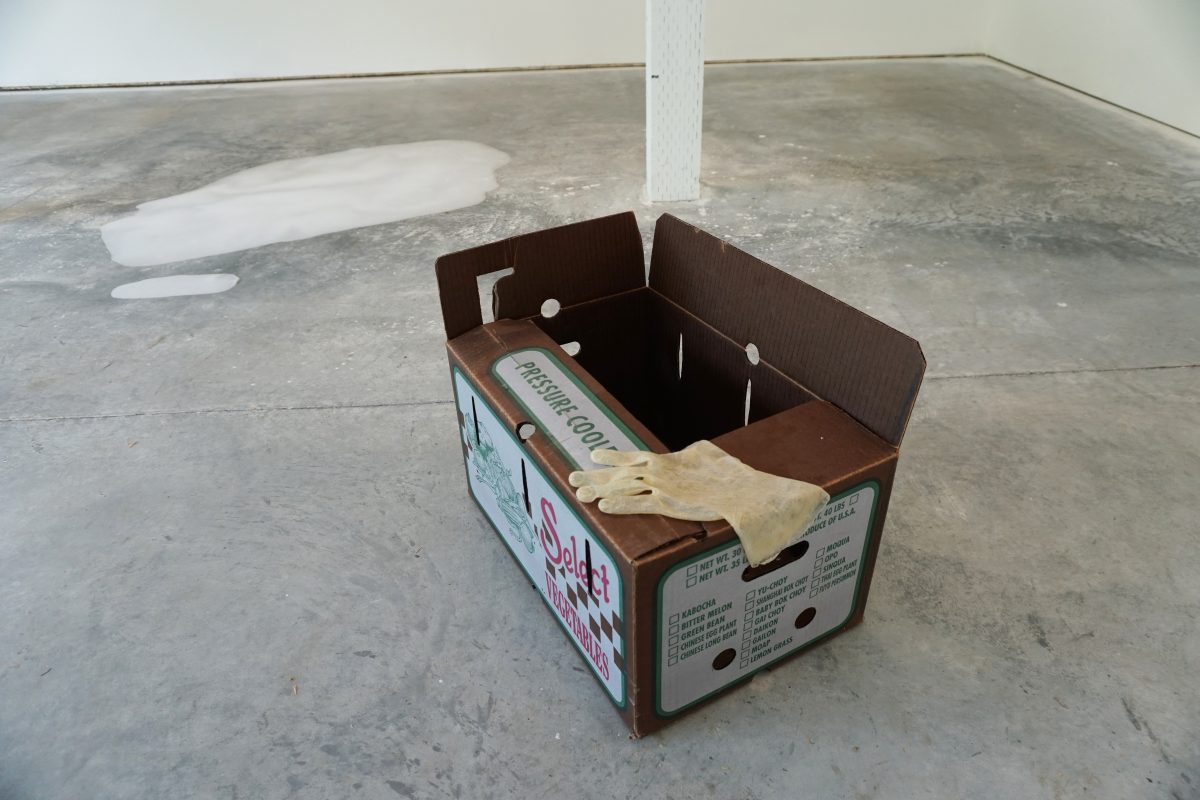

I have been living between Vienna, Los Angeles, and Montana for the past six years, which has

molded my artistic practice. My studio is often times packed away in a big red suitcase, laid out

on the living room floor as needed. I have found that molding and casting is a way to

produce sculptures that have volume, but don’t take up a lot of space. Many of my objects can

fit into the palm of your hand, can be folded into an envelope, or washed away when no longer

needed.

When I don’t have the space to set up a studio, my studio becomes the kitchen, which has led

me to discover many parallels between cooking and sculpture. Sculpture is, for me, a poetic

vocabulary of materials and ingredients, just like in cooking.

You work with a pantry and all the ingredients have their distinct origins and meanings, which

you combine to say something new. Viscous materials bind everything together; their physical

states change while you are working, melting together into something for consumption.

Just like cooking, sculpture is inherently manual labor. The hands and fingers that work the

ingredients leave their marks. In Korean, the word “Son-Mat” describes “hand taste,” the living

yeast and bacteria that lives on the cook’s hands, making each dish uniquely specific to the

person who prepared it. The same could be said about the production of objects.

Many of my objects need care. They are fragile and become brittle. They need to be protected

to survive.

A cast-iron pan lasts forever; an object made to be passed down for generations. Its beauty

depends on the appropriate care and the juices of the dishes cooked inside it. Its seasoned

surface tells a story of the evolution of dishes and cultures.

Cooking is the root of culture. We grow from it and it grew from us. It grew into a mirror of

culture throughout the history of human societies, which have melted together over time.