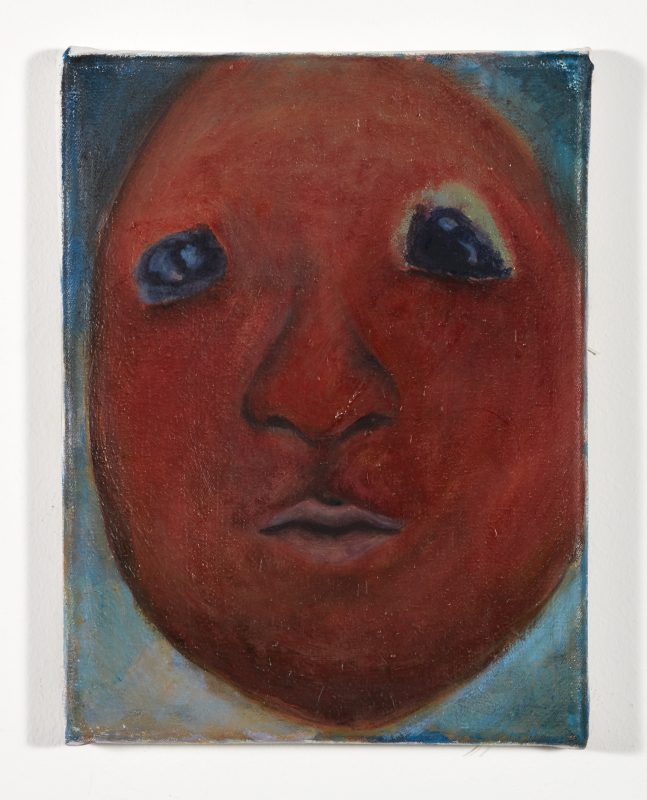

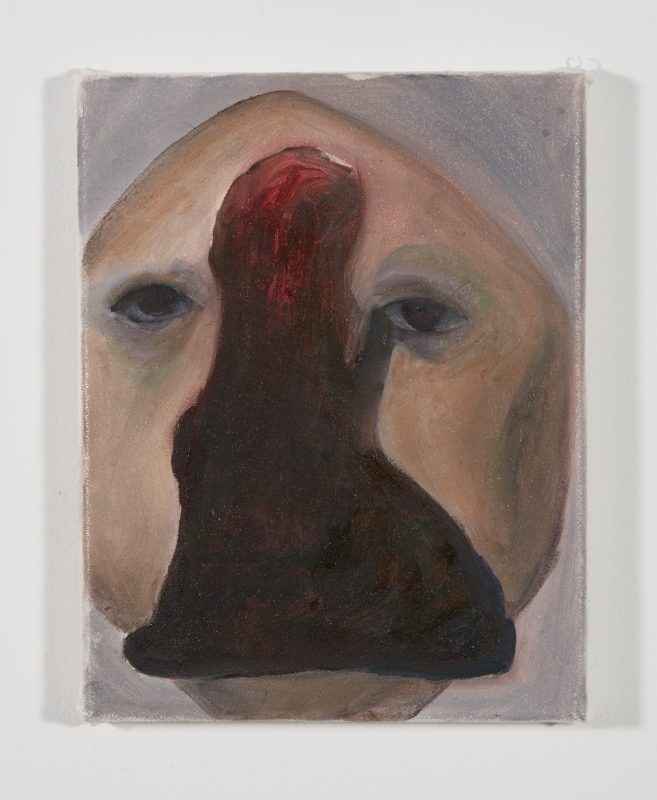

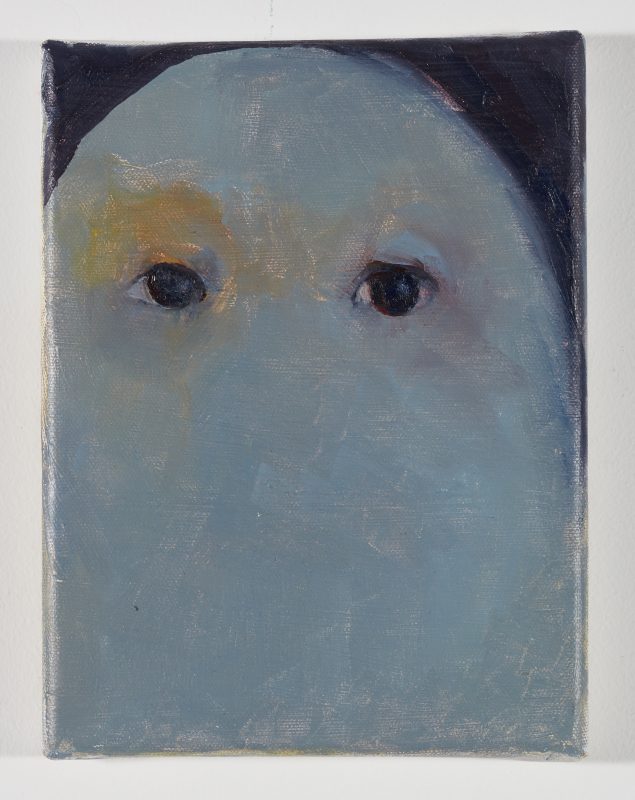

Es sind Gesichter, Portraits, Masken. Die Maske wird manchmal zum Gesicht selbst, und gibt an manchen Stellen ein anderes Gesicht darunter preis, wobei nicht klar ist, welches davon menschlich ist und welches nicht. Überhaupt ist nicht klar, ob es sich hier um Menschen handelt. Es könnte auch ein Stoff sein, der sich auf eine bestimmte Art und Weise wirft. Eine Vermenschlichung eines Gegenstandes, eine Sehnsucht nach einem Gegenüber.

//

They are faces, portraits, masks. The mask is sometimes a face itself, and sometimes the face underneath becomes visible, but it is not clear which of them is human. In any way, it is not clear whether they depict humans or not. It could also be a material that throws itself in a certain way. A humanization of an object, a longing for an opposite.

//

How to be you consists of paintings of faces and masks. Faces that seem to disappear into the background, that blend into the landscape, masks that could themselves be faces.

The faces are self-portraits, it is the self that manifests itself on the canvas, in the other, the opposite.

The You

I usually start with ‘something‘, a fleeting thought, a gestural painting, something that caught my eye, the neon lights of the Generali Center through the fog, a reflection in a photograph. I am not necessarily painting to put a predefined shape or a concrete thought on the canvas. I want to reveal something of my internal attitude. I strive to create a balance in the picture, which can be very shaky and lean to one side or sway, be it in colour or form. Nothing is fixed so that everything can also be something else. A person is not necessarily a person. It could also be an illusion of something, a random arrangement, like a fabric that falls in a certain way, in a certain light.

My work is process-oriented and I work slowly. Every layer is important, nothing disappears completely. The result is a canvas with patina. Layers, sometimes more, sometimes less, pile on top of each other, mix. It is an analogy of the self, where some things remain invisible to others and only express themselves symptomatically.

The image, whether it is a face or not, is me, a reflection of the self, a way to reveal something about oneself. The inside, that turns to the outside, that makes visible what might otherwise remain hidden, the disease that shows itself on the discoloration of the cheek and on the dark rings under the eyes.

Separation and connection alternate in the pictures, loneliness and relationship. The loneliness is existential, it transforms from a personal experience to a philosophical one.

How (not) to be seen

When one looks at a face, the lines between the self and the other blur, one doesn‘t know what one has put there and what has been there all along. I like the confrontation with the strange, the weird on a small scale. The unreadable in the everyday. The creation of a space for something that is easily overlooked, that is difficult to describe. Where something becomes visible.

Sometimes it seems to me that all my paintings are masks. Similar to Gillian Wearing‘s self-portraits, where human eyes look out of a human-looking mask. The mask may be flesh-colored, but it is immovable. It won‘t fill with blood, when it is ashamed and the lips won‘t turn white, when it is frightened. The mask is static. It does not adapt to the emotions of the wearer. Nothing happens accidentally, unintentionally. One has complete control. At the same time my masks are not a copy of something else, they function rather like inverted faces or surfaces for expressivity.

The mask allows the oddness, the inhumanness in the faces. A face that is deformed, that has a strange color, immediately reminds one of fantasy worlds. A mask lets it retain its place in a realistic world while not conforming to anatomic requirements.

Masks are inanimate objects endowed with a certain ‘affective power‘. It seems to be a primeval human need to breathe life into objects, to create a counterpart for oneself. The tenderness I can offer another person is similar to the one I apply to a painted face, or my porcelaine bowls before firing. I hold the objects in my hand, like a lover. This love, as they are my own bowls, becomes self-love, a manifestation of the love for the self.

A bowl is an object that one makes to hold something that one deems important. In its most primal form, two folded hands and later materialized in wood, stone, clay or metal, it is of enormous cultural significance. The bowl represents a connection between the self and the other, it is an intermediate thing, a catalyst to the other. It implies a meal, a gift or an offering.

Like a mask, there is always a connection to what it holds or protects. A mask without a face underneath and a bowl that never carries anything inside remains a pure object. Only through the connection with the living do they become what they actually are.

How to be both

I look at Caravaggio‘s young Bacchus, and I wonder, what makes someone a God? What does the young man in this painting have, that makes him a God? Is it the air of confidence, the casual opulence? Is it the knowledge in his eyes that he is not only the god of wine but a symbol, too, a symbol of what men can be when they are not riddled by the struggle for survival? A God is an archetype of man, a man who is strong but who doesn’t have to be. A man who can incorporate this strength and be sensual and almost child-like at the same time. A man who can be both.A God is therefore nothing more than a human idea of a counterpart who has everything. In this idea lie wishes and shortcomings of the human being itself, like a manifestation of the self, in the opposite.

How to be both is the title of a book by Ali Smith which has had a great impact on me. In it, the author tells two stories parallel to each other: that of a Renaissance painter, whose gender remains fascinatingly hidden, and that of a girl in the early 2000s. The two seemingly unconnected stories only come together in the reader’s mind, the theme of these two stories is the parallelity. How to be both describes not only the possibility of being ‘all‘ genders (and therefore none), it also expresses a vision of mankind in which everything may exist simultaneously.The

novel became the foundation of my thinking, it is a way of thinking about the world. The world in shades of grey or brown and how to endure it, which is precisely what makes it so fascinating.

The brown of decay

In this painting, as in many of Caravaggio’s paintings, the colour brown plays an important role. The entire background is brown. The space is not used to expand his subject, but rather to reduce it. It allows us to concentrate on the main character. But brown also becomes a symbol in this picture, all the fruit, the young man himself, will eventually decay and become brown. The transience emphasizes the beauty of youth.

In my work, colours are not only means to an end, the use of colour naturally determines the form, the whole picture. But I feel that I do not use colours to represent something, it is rather the other way round, I use form to show colours. The colour brown is a meeting of other colours. Brown is the compression of life itself, similar to a compost heap, I mix it out of the primary colors: yellow, red, blue. Sometimes the colour then slides in one direction, becomes a pink, a flesh colour. Brown for me is a colour in limbo, a colour in shade, but in the right combination it can shine just as well.

Brown holds this contradiction in itself: it is a colour of vitality. Life springs from the earth, it is the possibility of life itself. And it is decay.

Brown is realistic, it makes everything more realistic. Brown comes before black, but it is much more diverse, in black everything disappears, black is invisible to the eye, black is nothing. Brown is life and the coming and going to it.

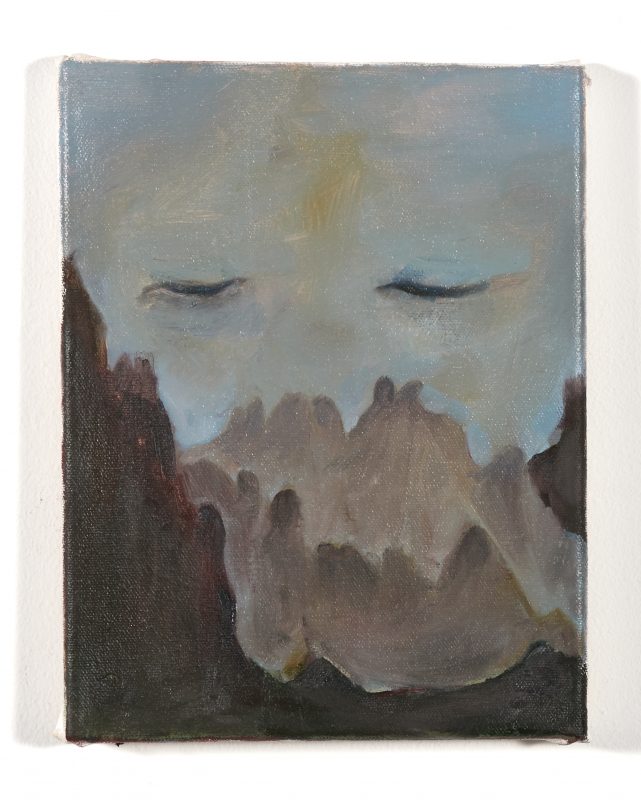

sleeping (2019), oil on canvas, 24×18 cm

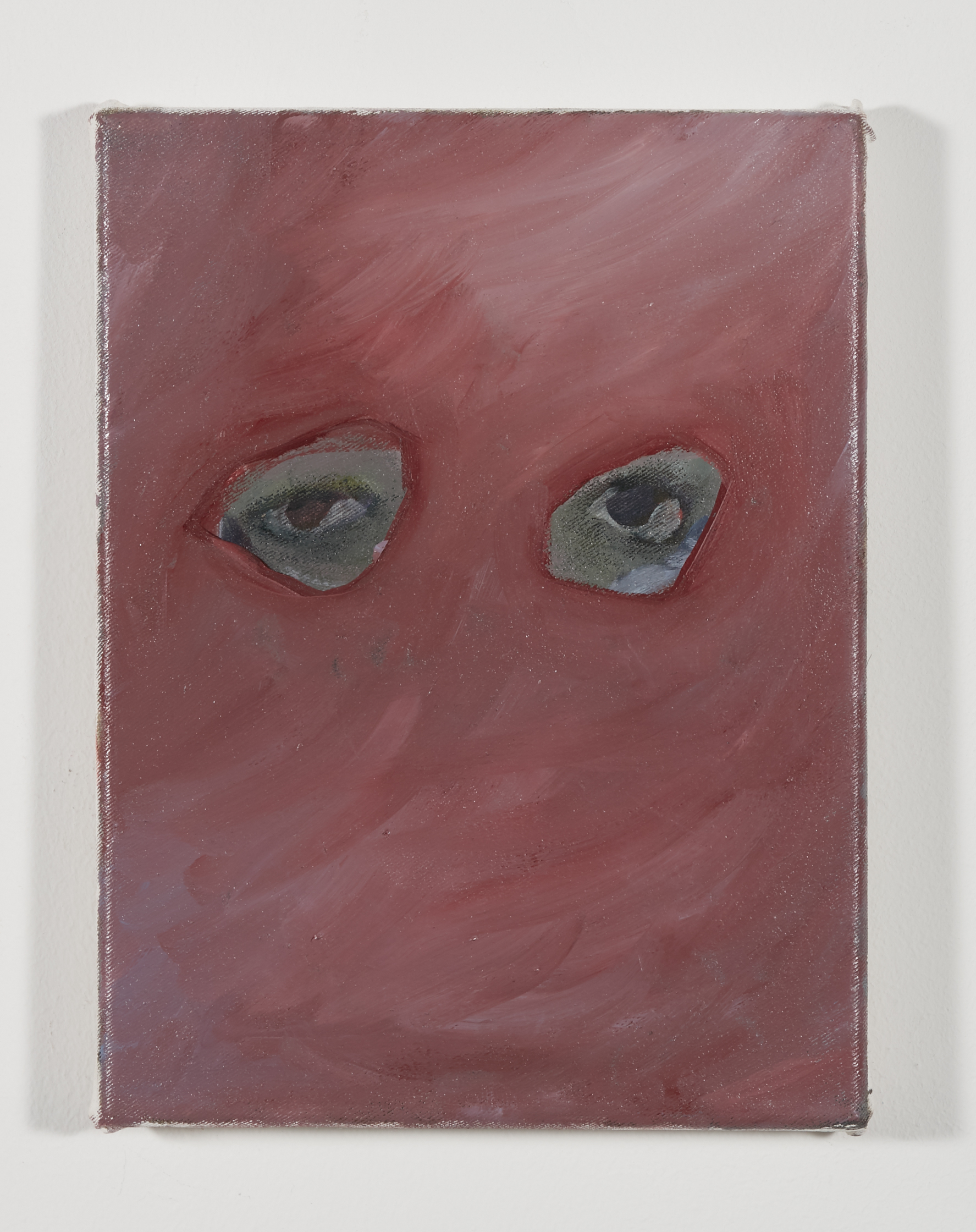

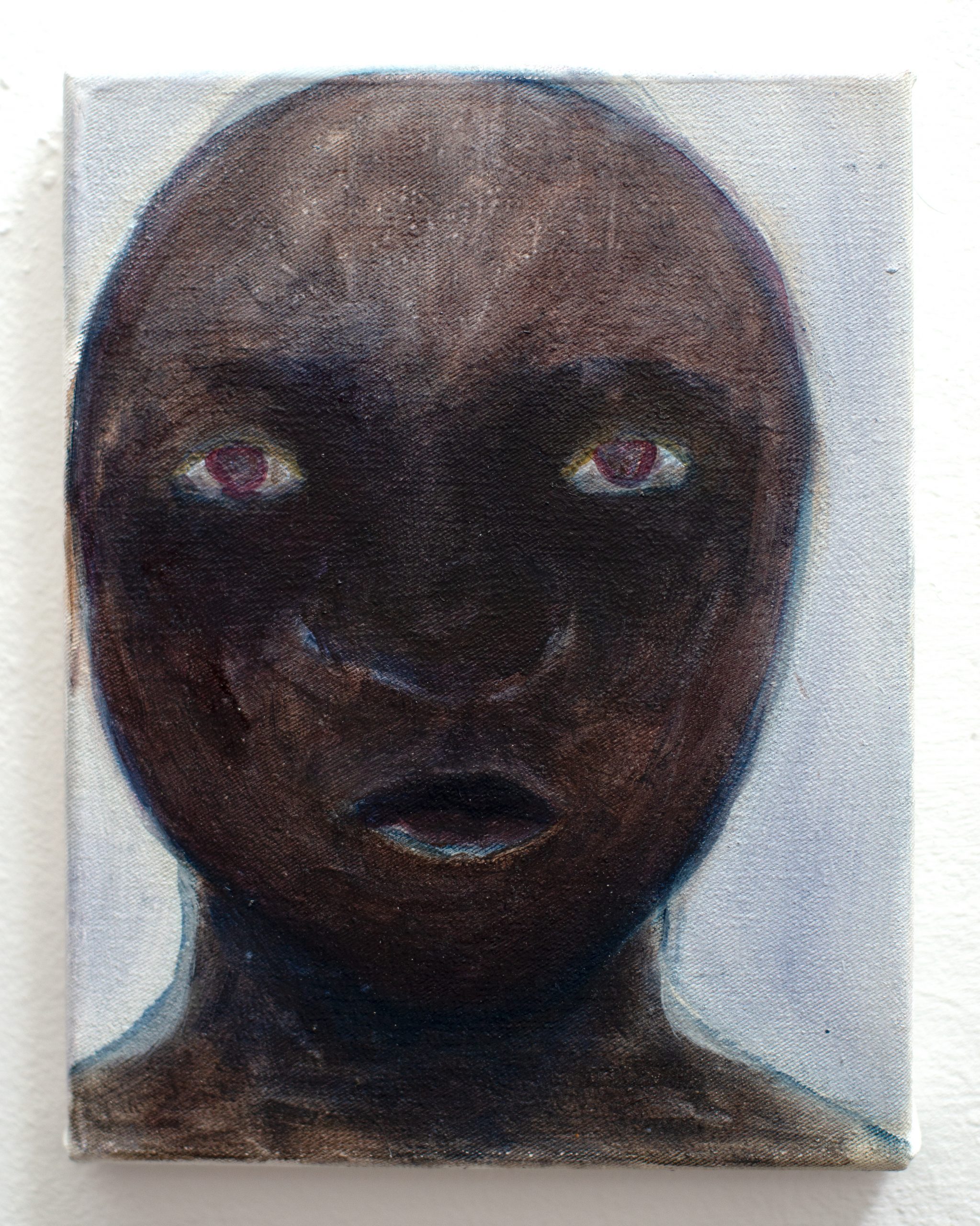

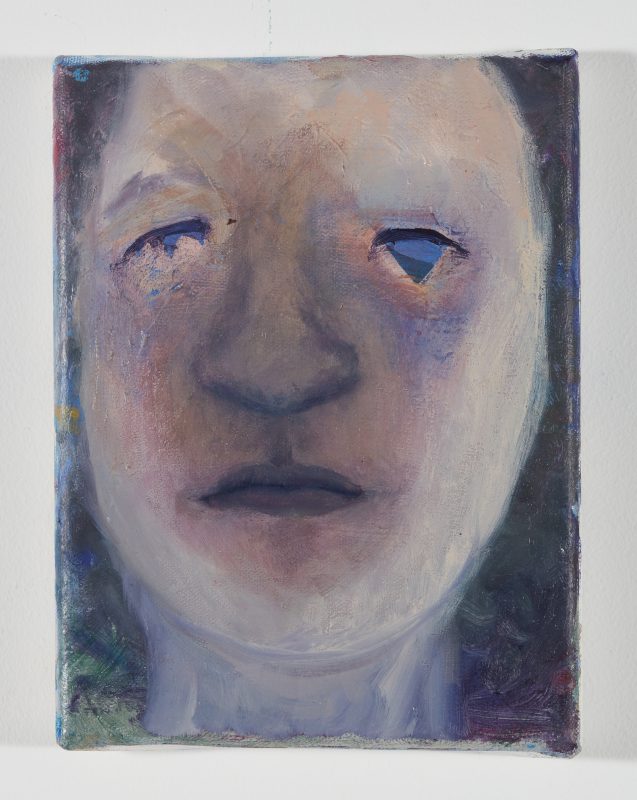

Untitled (2020), oil on canvas, 24×18 cm

Untitled (2020), oil on canvas, 24×18 cm

red, hot (2020), oil on canvas, 24×18 cm

Untitled (2020), oil on canvas, 24×18 cm

Untitled (2020), oil on canvas, 24×18 cm

Untitled (2020), oil on canvas, 24×18 cm

4 Jahre (2019), oil on canvas, 24×18 cm